The New Type of Commodity Trading Firms

Digitization: How it can be more than lip service and impact the bottom line.

This article will analyze and take in to account the changing environment and factors discussed in part one, and suggest tangible strategies trading firms could adopt to emerge victorious to stay ahead of the shifts underway.

Where are we headed now?

If disruption or innovation used to have negative connotations in the commodities industry, it is now needed and will be the key factor in trading firms survival in the future.

It is not all bad news, as the industry is slowly publicly admitting that digitization in the commodities market is here.

This realization could be catalyzed by the fact that their very source of profits or usual modus operandi is being threatened by external forces beyond their control. With extremely tight margins, less investment flowing into the sector the industry needs to think how it will come out stronger.

First, there will be some consolidation to weed out firms who are peripheral in the [commodities] market.

Example (I)

A (recent) example is Goldman Sachs cutting back its commodities trading arm, once a huge moneymaker and training ground for a generation of executives including former chief Lloyd Blankfein.

The retreat follows a months-long review under new chief executive David Solomon that showed the commodities business’s dwindling profits don’t justify its costs, according to people familiar with the matter. Executives believe the business is unlikely to repeat its heyday of the 2000s when it contributed as much as 15% of Goldman’s pretax profits.

Chief financial officer Stephen Scherr last month said there was an “active and engaged move to reallocate capital” away from Goldman’s troubled fixed income trading arm and toward priorities including lending and technology upgrades.

Example (II)

Astenbeck Capital Management founder Andy Hall is so highly regarded in the oil trading business that he earned the nickname “god.” But Hall has admitted that the value of his analysis has diminished in an age of automated trading. So much so that he closed his hedge fund in 2017.

Many longtime oil traders have found themselves confounded by sharp price moves that run counter to fundamental signals like the balance of supply and demand, stockpile levels and disruptions in oil-producing regions, The Wall Street Journal recently reported.

Then, there are 3 ways in which [surviving] trading firms could evolve to one or the combination strategies below:

Here, the key focus is value addition, and utilizing technology to create a sustainable moat.

#1. Business Model Innovation

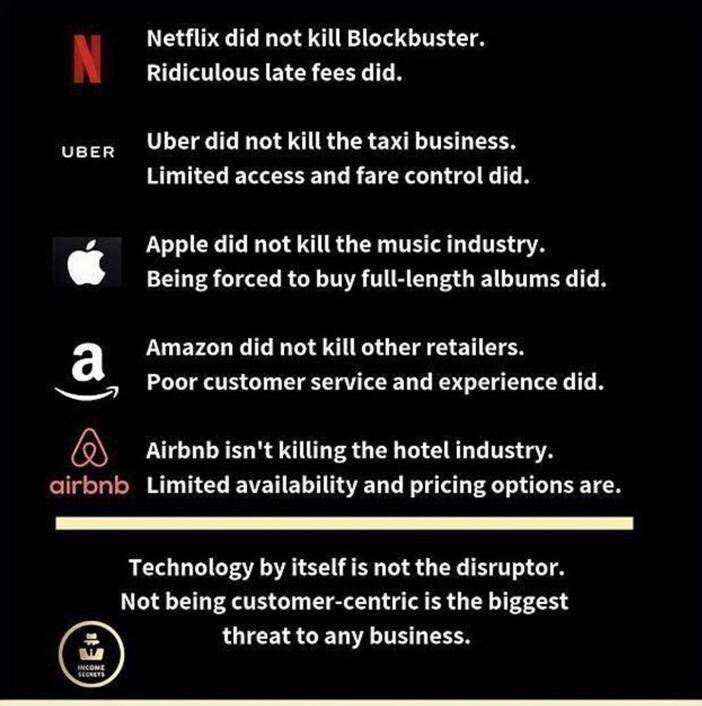

With the balance of power not on the commodity trader’s side, physical traders would need to have the customer at the centre of how they structure their businesses. Furthermore, simply providing financing to producers or banking on the arbitrage between different geographies cost of borrowing, will not move the needle in terms of value to customers.

One of the best-known examples of successful business model innovation is the “power-by-the-hour” business model of the British aircraft turbine manufacturer Rolls-Royce. It was definitely one of the early adopters of the subscription economy. To satisfy investors concerns on volatile earnings and unpredictability in forecasting revenues, “Trading as a Service”could be one of the ways to quell concern and differentiate from other trading companies.

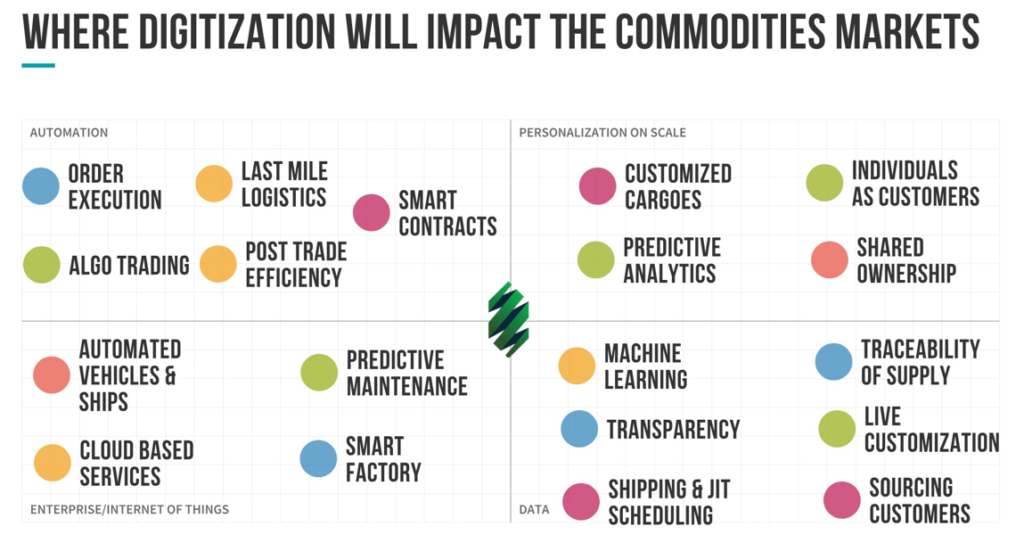

Other ways could be taking in to account how the industry will take shape, bearing in mind consumer preferences and then incorporating that in to your business model. For example, taking the “Super Just in Time” trend in to account could mean ensuring customers do not pay for excess warehousing or costly shipping or demurrage charges. Otherwise, “Personalization on Scale” could mean utilizing technology or service providers to provide timely services that go beyond buying on FOB (loading port) and selling on CFR (discharging port) to customers.

#2. Niche focus and unbundling

Previously, the cost of setting up a business was so prohibitive that the number of new companies starting out was low. However, if we take a look at the finance sector or FinTech, we see new entrants eating away at major historically “too big to fail” banks by focusing on a niche and banking on new customer trends and demands.

Whilst some consolidation would occur, some firms (existing or new) would thrive in more niche markets, where they focus can focus on:

(I) Frontier markets which lack major banking infrastructure or have limited reach due to sanctions or export restrictions (Iran, Venezuela, Mongolia etc).

(II) Relatively new commodities which are poised to grow in the new energy mix (Cobalt, Palladium etc). This is probably already saturated given the global coverage on electric vehicles but nonetheless could see new producing nations who emerge to take advantage of high prices.

However, these niche firms would aim to keep the cost as low as possible and outsource non-core (trading) functions. For example, accounting, operational management etc. This “unbundling” of a typical trading desk means these niche firms could have several providers on a subscription basis at a fraction of the cost than having them on their books as permanent staff. Like the gig economy, but for commodities. This would then also spur investment into innovative companies in the commodities sector (what I refer to as #Commoditech).

#3. Margin protection & Economies of Scale

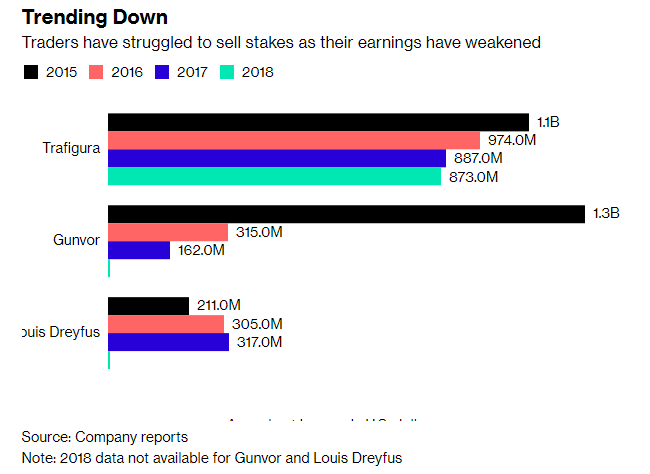

For the incumbents who adapt, they would be compensating for reducing margins by increasing volume and market share and focusing on profitable desks.

Trafigura’s chief executive Jeremy Weir said big commodity traders would only get bigger. “They are difficult businesses, and very diverse businesses and they have to adapt to markets,” he said, adding that in that environment “the big get bigger”.

However, if these firms only acquire for market share or volume with no other innovation, then net profitability per asset decreases whilst risk increases — and that does not bode well for return on equity for its shareholders or future investors.

To take advantage of size, one way would be to follow the large banks ie to become an integrated provider or industrial company. For example, from owning upstream assets such as mines or plantations to distribution and consumer-facing downstream (for example petrol or electric vehicle charging stations or producing a new form of vegetable oil or consumer good).

This strategy depends largely on utilizing technology to reduce costs (as with scale comes large human capital costs). Any dollar saved would add directly to the profit and this would be noticeable especially with typical trading firms used to 1–3% margins.

Technology in Commodities — a pipe dream?

In such a traditional industry, it is unrealistic to expect a change in mindset and strategy to happen overnight. Furthermore, as margins are compressing most firms would be focused on the short term (ie survival) either securing funding for daily operations or meeting trading volume targets.

Thus, unless technology directly impacts trading firms P&L (or share price), it would most likely be put on the back burner until better times.

However, given that technology is an enabler, and core to most trade processes, it would be myopic to ignore this. Rather, it would be better to analyze which technologies or area taking into account each firm’s budgets or priorities and formulate a plan of attack.

For example, a trader focused on mining or metals could focus on cutting costs to improve returns and thus focus on operational efficiency in the form of automation. This could mean automating contracts, reducing costs in operations teams or utilizing technology to reduce the cost of order execution. They could also combine that with cloud-based services of non-core facilities rather than utilizing on-premise expensive services.

Another firm could focus on building their niche and growing customer base by using data to source new customers or commit to fulfilling ESG initiatives by leveraging off technology to ensure traceability of supply meets customers’ criterion.

Conclusion

Technology is the glue that binds futures trading firms and a catapult into the next era of commodity trading. If used strategically and incorporated into firms core businesses, it would enable trading firms to be more customer-centric, add value and thus, ensure not only survival but prosperity.

The fact remains that commodity trading is one of the oldest industries. It is central to the global economy and in fact powers it.

However, like how the automobile industry was comfortable and though it’s the 100-year advantage of the engine was formidable, most countries and even incumbents have had to swallow the bitter pill of the electric vehicle. Again, the innovation here was a result of a change in regulation, consumer preferences as well as disruption in the industry. It is the tipping point for commodities firms, and an interesting time to lead and shape the future ecosystem.

Published on Medium

READ MORE

- Malaysian Natural Rubber Production Holds Firm; Unified Efforts to Boost Output

- Consumer vs Supplier: race to rubber sustainability

- Inflation Risks Triggers Anxiety as Supply Constraints Persist

- Rubber industry grapples with aftershock of China’s crackdown

- Commodity Pricing: the Need for Transparent Pricing to Benefit Supply Chains and Address ESG Risks

- Data and Innovation Key Requirements for the Future of Trade Finance

- The Future of Pricing ESG Risk

- Commodity trading and ESG: using technology to support sustainability in the natural rubber industry