The New Type of Commodity Trading Firms

The 4D’s: Disruption, Digitization, Declining Margins & Data Democratization in Commodities Trading

Disruption; lauded in Silicon Valley with at least 47 startups that were catapulted to unicorn status in 2018 alone. It is also often celebrated amongst consumers which means more choice, cheaper alternatives or just something new.

The (literal) fact remains that, “disturbance or problems which interrupt an event, activity, or process” is the opposite to the mantra of “if it ain’t broke, why fix it” (read: If I am making USD20/MT per unit of coal or cobalt) I will continue doing this…. until I can’t. Or if you were lucky enough to have been trading since the golden era of the 1990’s and early 2000’s — long enough to own the latest yachts or holiday homes — you would be happy for any additional year until retirement.

This 20 dollars may sound small, but let’s break this down. Assuming a bulk commodity like iron ore or coking coal, USD20/MT profit of a typical vessel size say 150,000MT means USD3 Million made on one cargo sold. Sure, taking in to account operational and financing costs that could bring profits down a little, but still, a substantial amount.

Now there are obviously different margins for various commodities, but the premise has always been the same: buy from a producing country, typically in a developing nation and sell to industrial nations and make a profit. Do that many times without screwing up (buyer defaulting, force majeure, seller defaulting, claims on quality etc) and you are rewarded.

The democracy (and accountability) personally for me was addictive — you are rewarded largely on your performance, your “book”. Of course, the potential financial gains were too and that too with China’s insatiable demand for every spectrum of the commodity.

In the past, physical commodity traders added value by utilizing or capitalizing on the 5 factors below:

1. Access to cheap funding relative to emerging economies

Here, imagine you are a steelmaker in India or a miner in Indonesia. Your main concern would be access to working capital as you run a capital intensive business. Commodity trading firms typically added value by having access to cheap financing due to their size and location and relationships to banks. They also put up the traded cargoes as collateral often to get better leverage or terms. Again, borrowing costs in developing markets (like India or Indonesia) are traditionally higher ranging from 14–18% compared to 3–5% in financial hubs like Singapore or Switzerland where most trading firms are present in.

Thus, there was inherent value in trading firms bridging this (financing) gap literally and possibly keeping a spread. In return, to providing longer working capital (think credit card payments which happen after you received your goods or purchased your air tickets) or prepayments (paying for your goods before you receive them), trading firms get access to “offtake” (imagine being a distributor or exclusive agent of Nike for example).

However, just as Nike eventually established a global presence in most markets, and reduced its 3rd party or agent businesses, this same scenario also plays out in commodity producers. Smaller B2C firms in retail also established themselves online and focus on direct communication and marketing to consumers, facilitated through platforms like Instagram and other social media sites. Again, this would also be a niche or smaller miner’s preference if they had that option.

2. China’s unprecedented growth and an insatiable appetite

For commodities, since the start of 2000, the statement of “when China sneezes, the rest of the world catches the flu” pretty much sums up how entire industries have grown on the back of China’s industrialization or modernization.

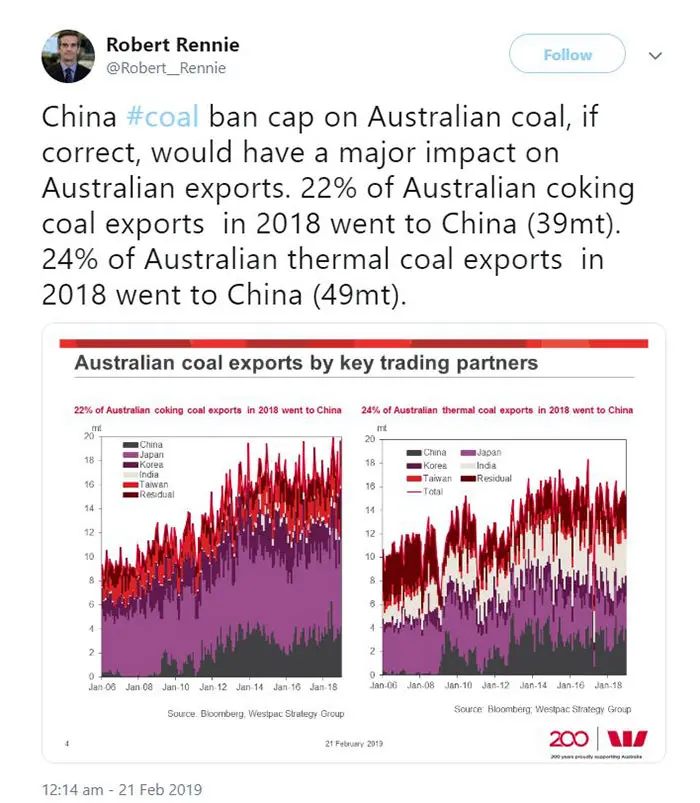

Many nations who rely on raw material exports, especially those with closer proximity to the Asia Pacific such as Australia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Africa are heavily reliant on China for their prosperity. This is still the case today, as China’s restrictions on Australian coal sparked panic in the markets(Australian stocks and even politically), see image below.

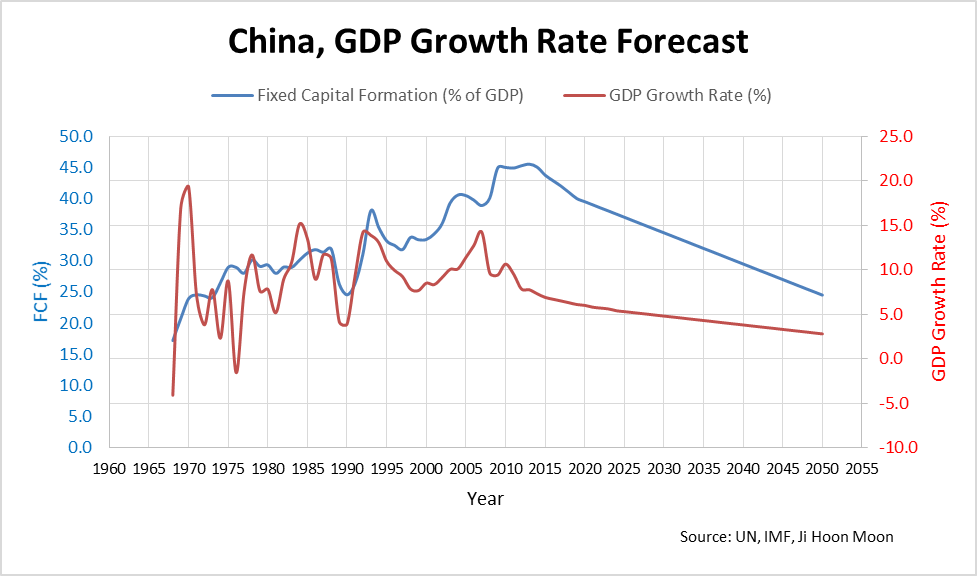

As a result of China’s demand across the board for raw materials, coupled with unprecedented decade long double digit growth (until 2012) money and investment continued to pile and flow into all avenues exposed to commodities. This meant funds exposed to commodities, ETF’s, miners, trading firms, equipment firms all experienced exponential growth.

Although China still drives most of the demand for commodities, they are past the era of double-digit growth, and with widespread urbanization, they will look to move up the value chain, and growth drivers will rely more on its service economy.

3. Information discrepancy which gave asset owners an edge in terms of proprietary information

In the past, operating warehouses, having good relationships with port management or shipping and customs agents or even owning assets meant you had privileged access to crucial supply and demand information. This could mean anything from port queues, stockpiles at warehouses, production figures, shortages etc. It was like being in an exclusive WhatsApp chat where you had access to information which you could use to form a market view, and eventually make an assessment on if the market would go up or down and act accordingly. Of course, the cost outlay was in owning and operating the assets, but that was a small investment compared to the returns generated.

However, with technology blurring the lines and democratizing access to information by way of satellite tracking for ships and cargoes, that advantage is slowly diminishing and the return on holding or operating assets is minimal. Now, it is also common for quants and algorithms to dictate futures prices and pricing dynamics.

4. Opacity — leaving the industry largely unregulated

The tipping point for banks: Dodd-Frank. Many banks said that the 2010 Dodd-Frank regulation left them little choice but to exit trading physical commodities, as it meant higher capital requirements and that limited their day to day trading operations and handcuffed their staff.

Other regulations such as the Volcker Rule — have forced banks to cut down on speculative trading. Basel III capital rules — have limited proprietary trading and the amount banks could leverage to make money.

However, a large segment of physical traders are privately owned (Vitol, Trafigura, Mercuria, Gunvor, Louis Dreyfus etc). This meant they would not be subject to the same regulations and were left to continues business as is. Even those that were listed were left to their own devices mostly as they were not deemed as financial institutions nor were they exposed to retail clients, unlike the banks.

Note the timing: in 2010, see point #2 above on China’s double-digit growth — this was great news for all trading firms, less competition on the street and cheap assets (which had good ROI and information access, see point #3) ripe for the picking.

Of course, nothing is static — with latest measures rolling back some Dodd-Frank regulations,easing restrictions on all but the largest banks. It raises the threshold to $250 billion from $50 billion under which banks are deemed too important to the financial system to fail. However, it is unlikely banks who have previously exited will jump back in full swing in to physical commodities as of now.

5. Fragmented world

This isn’t really a separate point, but rather a culmination of the above four points and the new forces that drive or dictate the new economy, and hence the commodities market and its participants.

Previous advantages have been clouded out by low-interest rates, producer countries expanding directly into consuming nations, more informed buyers and sellers, technology democratizing information, and just plain old competition.

For example, take the Indian steel manufacturer or Indonesian miner — in the past, they were constrained by limited access to the global economy and large costs and barriers of setting up abroad. This cost has reduced and marketing costs reduced by online presence only serves to exacerbate this trend.

Furthermore, the world’s biggest buyer of all things raw material; China is also taking matters into its own hands in this turbulent environment of trade wars and political protectionism. This strategy of vertically integrating and having more influence on key raw material supply chains predates the recent trade war news. For example, ChemChina and Syngenta, ChemChina and Pirelli, ICBC and Standard Bank as well as COFCO acquiring NobleAgri and grain trader Nidera. These acquisitions are highly strategic, ensuring either food security for China, locking in raw materials as close to the source as possible, and propelling its ambitions for “Made in China 2025”.

Up Next…

Part 2 will look at what kind of firms will thrive and how to adopt strategies to prosper in the new trading ecosystem.

Published on Medium

READ MORE

- Helixtap China report: Weakness prevails Amid Oversupply, Trade Tensions, Soft Demand

- Tire giants redraw India playbooks; Indian firms rework overseas

- Chinese tire giants accelerate global expansion amid trade barriers

- Indonesia defies headwinds to post robust rubber exports in early 2025

- Tariff war, weather hit Thai rubber exports hard in April

- Exports nosedive, but Sri Lanka’s rubber industry aims high

- Wintering, labour shifts cripple Malaysian rubber output in April

- Indian Natural Rubber production marginally improves, consumption down