Coding and Commodities

How both worlds collided and the lessons learned.

In March 2018, I registered my startup in London. Having worked in the commodities market since 2012, it was a leap of faith (on my family, partner, and myself as a Singaporean typically thriving on stability) to foray into the unknown. The unknown especially given the industry’s default position on disruption. The vision and idea and a belief that the tides are turning and that we should be the ones ushering commodities trading into the next era.

This isn’t an article about the ups and downs of being an entrepreneur (there are lots more books, Medium articles and websites focusing on that), but rather a (public) note of my observations as a non-technical founder in a traditional industry. The lessons learnt, a reflection one year in and the underlying theme of timing and cycles.

Cycles and Timing — You Can’t Predict Everything, But You Can Prepare Your Best To Ride the Wave

Here, two great examples are from Howard Marks (the equivalent of Warren Buffet in distressed debt) and Geoffrey Moore (who’s first book, Crossing the Chasm, focuses on the challenges start-up companies face transitioning from early adopting to mainstream customers).

Crossing the Chasm

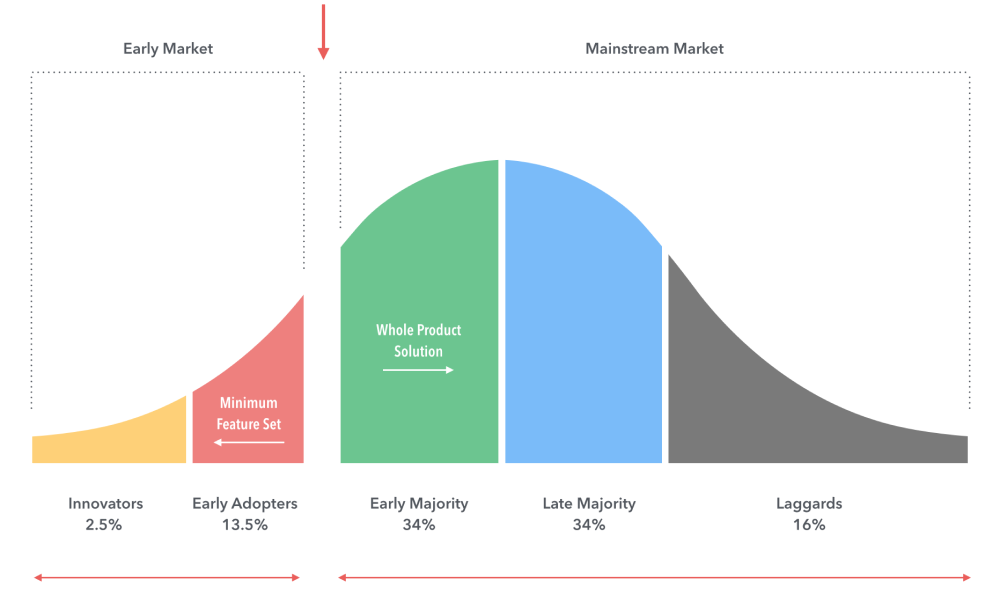

In Moore’s diagram below, the chasm is where the idea (and most startups) die. Startups were previously having decent feedback from early adopters suddenly need to make payroll or rent or if externally funded, hit specific milestones, but the rest of the market just isn’t taking to it. Lack of results, bad timing, consumers unaware of product or lack of product-market fit are all death knells, especially for undercapitalized firms.

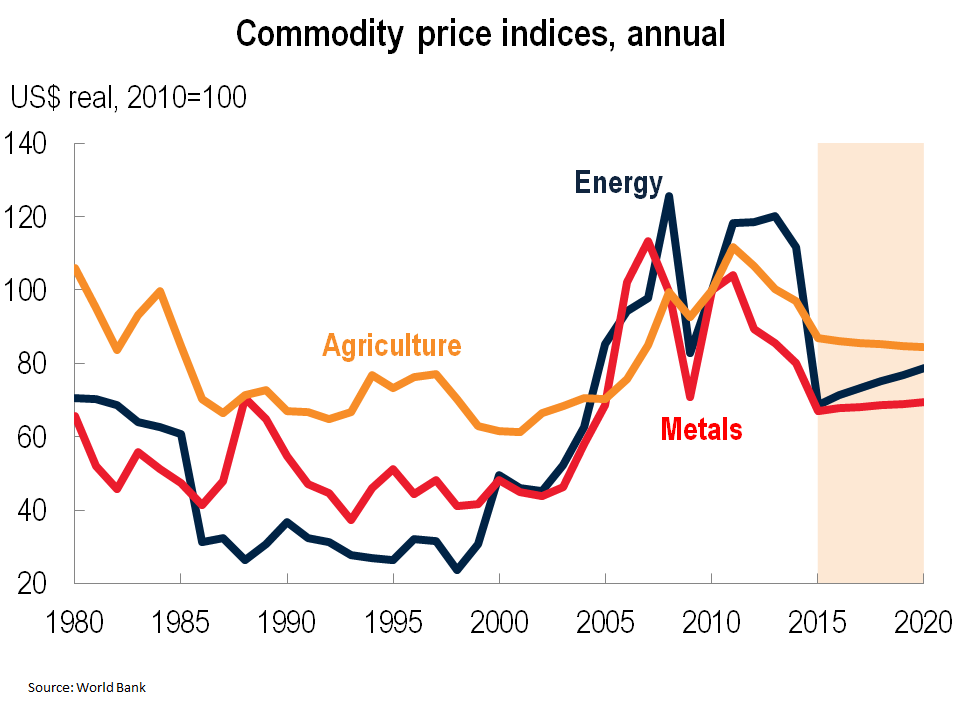

Market Cycles

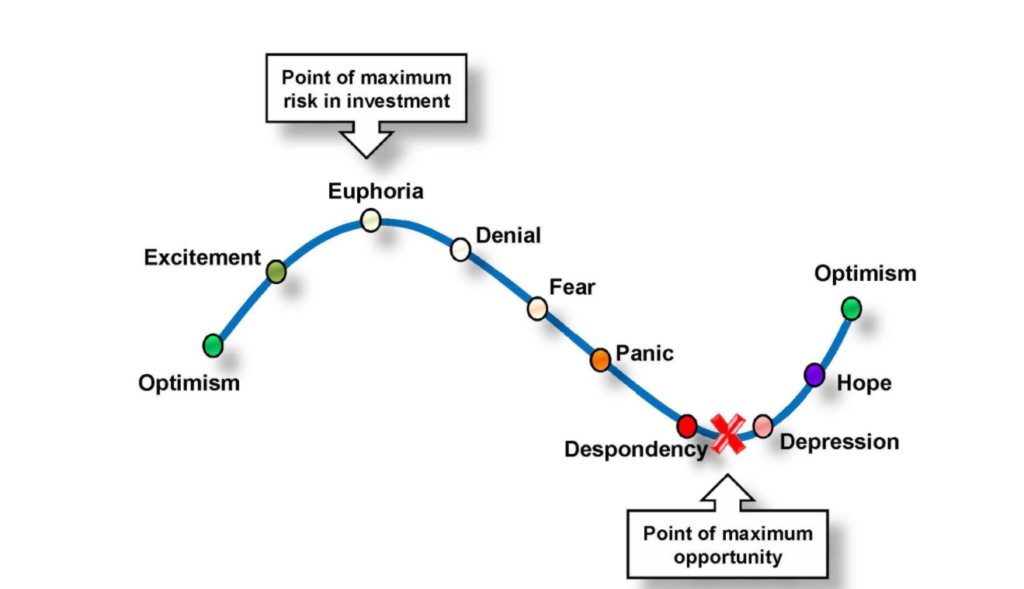

In the image below, typical of market cycles (and also could be used to represent early adopters and the majority in new product adoption), the key to success also goes back to timing, and some basic understanding of which part of the cycle you are currently operating in.

Commodities — and those in the commodities market ecosystem are used to operating in cycles. Take for example a wheat farmer who may have lower prices when an overall bumper crop arrives due to good weather (usually seasonal and can be predicted or factored in) or sustained lower demand due to the popularity of low carb diets widely adopted (unpredictable event but great impact on the farmer and industry as a whole).

Either way, it is important for the farmer to take note which part he is in the cycle. For example, China’s insatiable demand could mean increased demand overall for food and create a lot of optimism in the industry, which also creates peripheral suppliers (those who want to take advantage of high prices only), eventually supply catching up to demand and normalizing or even reducing prices. Entering the market at its peak (or when everything is rosy) could turn out to be risky, is just the same (risk wise) to not have tried at all — if the farmer truly believes in the value add of his wheat to the global supply chain.

Find Your People, Better Yet, People Who Aren’t (Exactly) Like You

Our team consists of individuals with expertise in strategy, commodity trading, technology and data science, alongside industry veterans and entrepreneurs. This mix was serendipitous as it was trial and error — and a small team wearing multiple hats.

However, starting out, one of my main hires was for a tech lead, given I was a non-technical founder.

Speaking the same language (Internally)

Given our different backgrounds — mine in commodities sales and trading and our tech lead’s in programming, we naturally, spoke in different languages. Our initial emails and discussions meant taking the long route, breaking things down for each other and educating each other in our respective fields.

It taught me two important learning points:

- Sharing the vision of where you want to take the industry to — as failing to do so would only mean wasting each other’s breaths in learning to understand the ‘language’ barrier.

- I (we) all tend to speak in jargon — and as Einstein says, “if you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand the concept yourself”. Having a different perspective or teammates who have different (education or training) to you forces you to break out of speaking in jargon, and distil the idea and thus get a fresh opinion on things.

Prioritising: Marrying Form, Function and Futurism

Being an enterprise-focused solution, we had to marry cutting edge and excitement of the latest technology with a heavy dose of pragmatism. The paradox of making it suit our traditional clients but also not compromising too much on the basic tenet that we aim to move the commodities industry forward, using technology.

For our tech lead, that meant prioritising a few things:

- Security: Here data protection and protection from malicious attacks were key

- Simplicity: User experience had to be a core tenet for us, given the traditional industry we operate in.

- Scalability: Factoring global teams, accessibility whilst being on the road or in a factory or mine was also key. Furthermore, adaptability across various types of commodities was also important for expansion.

- Speed: Our rationale for this was simple, if the old way was simpler or faster — why change? Thus, we tried to take in to account this when building features and creating the backbone of our product.

Sure, we started out with a less than a structured framework, but as with most startups constant communication with potential customers and internally — we learnt which segment of customer would be our initial focus and what we didn’t want to be known for (a small add-on rather than a way to future proof customers business).

Read, Revise, Repeat — The Lean Startup Way

This was a tough one for our team to learn. At the expense of being customer focused we initially took whatever our prospects or initial focus group said as gospel truth and worked that feedback or suggestion in to our product.

There are varying quotes from thought leaders or visionaries which basically state the same logic.

We learnt along the way two very important lessons to frame our processes.

(I) Proof is in the (always improving recipe) pudding

Here, building something to show in a demo or minimum viable product (MVP) works wonders (cost-efficient and allows us to personalize according to each customers pain points). But more importantly, allows us to progress further in terms of real customer feedback (and commitment) by seeing what is an actual demo or use case.

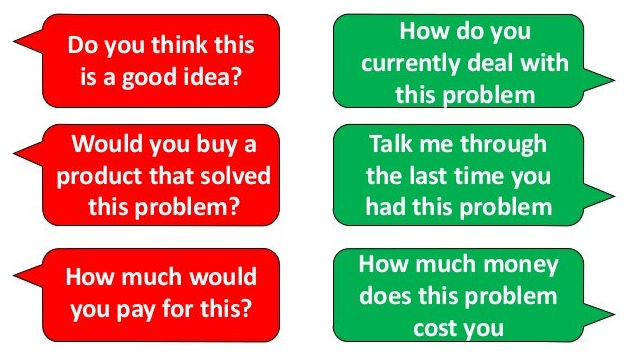

(II) Pass the Mom Test

This is critical especially if your clients are more indirect or if you know them on a personal or professional level. Kind of like the “does this outfit make me look fat?”, most of us set questions to test our hypothesis or do market research, but framing the questions is really the most important battle.

Some (useful and tangible) examples of questions to ask to pass the Mom test in the image below. The book’s premise is that given that everyone is lying to you, how do you understand if your business is worth pursuing?

Having these two thoughts underlying our process also means we have to always improve and expand our use case scenarios.

Follow The Money

It could be a coincidence, but at least 3 people have responded with “Follow the Money” when discussing the next cycle and trends going forward in the commodity market.

Analysing this seemingly simple 3 words, I realise this could apply to both understanding market trends and cycles as well as finding potential types of clients to work with.

Think outside the box (and play to your strengths)

Instead of trying to strike it rich by looking for gold (requiring a lot of effort and unpredictable return), he chose to capitalise on the Gold Rush by selling the dream of striking gold — and cornered the shovel market. In the week between learning about the discovery and yelling about it in San Francisco, he’d bought all the picks and shovels in the city. He already owned a provision shop, and just ensured he benefited from the trend.

The merchant’s business is not dependent on anyone person finding gold or riches but is driven by a supply of customers who dream that they might.

What is the “Gold Rush” in your market

Could Sam Brannan have predicted or imagined that his area was the site of the first “Californian Dream”? No. But was he quick to pick up on the trend and act on it? Yes.

If people are seeing their fortunes change overnight or at least having the hope that they could potentially strike metaphoric gold, that represents the mindset of your potential market. That hope and possibility mean entrepreneurs can try to follow the money by providing services to willing participants driven by the booming market.

Similarly, if the market is a post-depression era or is fighting for survival — strategies need to evolve. The first being showing customers how your company is the lifeboat in what feels like a sinking ship for the potential market. Or if they refuse to see the signs, find another market who is in a different, more upbeat stage first to tide your business through.

Where We Are in the Cycle…

For commodities, looking back at the market cycle above, we are most probably near the bottom of the market in the “fear” just before desperation and panic.

Sure, there are pockets of the markets which have a lot of optimism for example in the raw material segment for electric vehicles (Palladium, Nickel, Cobalt) or more recent developments in energy (LNG, LPG). The uptick in prices (coupled with general market optimism) could mean opportunities in supplying “shovels” to these markets.

Alternatively, recently less loved markets like thermal coal or shale and oil could mean budget cuts as companies look to appeal to their shareholders. This could also mean opportunities, as these companies either become under-served or look for cheaper solutions (budget “shovels”).

What it Takes to Cross the Chasm

Before the Gold Rush, the first step is ensuring your business is viable. No one can predict when the gold rush happens, but most people starting out have a conviction or vision of where they believe the market is going, and how their solution helps their customers in finding gold.

It may take many MVP’s or pivots until the cycle or trend turns favourable, but to end off with Howard Marks again, “we arrange our lives in expectation of what we think will happen in the future. In general, we get the desired results if future events conform to our hopes or expectations, and less desired results if they don’t.”

At Helixtap, we believe the future of commodities and the firms in the ecosystem is undergoing a structural change — new trends that could spark disruption and alter the very nature of commodity trading. These could unlock potential growth or spell demise for certain firms.

As Tencent CEO Pony Ma says, “we are stepping into the second stage of the Internet, the Industrial Internet era and with the digitalisation process ongoing, the main battlefield of the mobile internet has moved from the consumer internet to the industrial internet”.

For commodities companies wishing to either embark, enhance or leverage off digitisation initiatives — need to work with technology-focused companies who understand the commodities market.

Published on Medium

READ MORE

- Tire giants redraw India playbooks; Indian firms rework overseas

- Chinese tire giants accelerate global expansion amid trade barriers

- Indonesia defies headwinds to post robust rubber exports in early 2025

- Tariff war, weather hit Thai rubber exports hard in April

- Exports nosedive, but Sri Lanka’s rubber industry aims high

- Wintering, labour shifts cripple Malaysian rubber output in April

- Indian Natural Rubber production marginally improves, consumption down

- Tire trade at tipping point after US Q1 import shifts